Categories

Archives

The Road to Quiruvilca

You might think that a career working with mining companies and executives around the globe was surely a ticket into countless famous mineral localities everywhere. Oh, if only. (In fact, of the thousands of active mining and exploration projects worldwide, most are not famous mineral localities, nor do they produce anything approaching fine mineral specimens.)

So when my friend Adolfo Vera called me at home late one cold December night to talk – in his capacity as President of Southern Peaks Mining Company – about a new deal, I could hardly contain my enthusiasm. (Ok let’s be honest, I didn’t actually try to contain it.)

Adolfo: “Ray, can we talk about negotiating the purchase of a mine in Peru? You may never have heard of it – it’s called the Quiruvilca Mine.”

Ray: “Umm… I’ve more than heard of it…” (After all, it is one of the most important mines in Peru’s history, famous among mineralogists and collectors for fine specimens of many minerals.)

Adolfo laughed and responded that if we were successful, I was welcome to catch the next plane and he would love to host… and when we did finally close the deal, I took Adolfo up on his kind offer and set off on an adventure to Quiruvilca with my collecting partner David Joyce (www.davidkjoyceminerals.com).

A trip to Quiruvilca is a bit involved. Like many of Peru’s most famous polymetallic mines, Quiruvilca is high in the Andes. After a flight to Trujillo, the drive from sea level takes a few hours, beginning among sugar cane plantations.

The main highway services not only Quiruvilca, but other towns and mining developments, including Barrick’s Lagunas Norte (Alto Chicama) project.

Although construction and improvements continue on the road, it was still a treacherous affair at the time of our visit. (A week later, a bus with 60 people crashed off of this same road into the river gorge, killing all on board.) The highway is full of large vehicles with interesting cargo.

And this main highway gets messy during the rainy season…

Traffic is all over the road. Coming around one corner, this is the view out the front window. (Yes, the front.)

In part, vehicles are all over the road because of the potholes. You can see a few small ones in the photo above, but here is a view of larger ones – each one enough to swallow even a tanker truck.

The highway climbs up and up, into the Andes. Many afternoons in the rainy season all you get are glimpses across the mountains through small holes in the clouds.

Once you get to Quiruvilca, you have climbed to an altitude of 3800 metres (12,500 ft). By the way, the name “Quiruvilca” means “sacred tooth” in the Quechua language, and refers to this formation (photo below) which rises off the top of the mountains into the sky (and which is actually a few kilometres away from the town and mine).

Company Area

Upon arrival at the Quiruvilca Mine, we were invited to stay at the nicest residence within the gated executive housing area, near the company offices and labs. A wonderful place to stay, this complex dates to the time when Asarco owned the mine. (As the town of Quiruvilca developed as a typical mining company town, I am not sure if there would even have been any public accommodations, had we been independent visitors and not guests of the mine). As it was, we were spoiled.

Our house had a nice fireplace (helpful, as it was chilly during our stay, between 4 and 10 degrees C).

In the vicinity of the housing area and the company offices, there were trees, and yet you could still catch glimpses of the valley and mountains beyond.

Looking back at it all from the hills across the valley, the view includes the mill at the top, the company offices in the middle section of trees and our housing area was in the group of trees below and to the right of the middle of the photo.

Looking at the above photo for context, the Quiruvilca Mine and the town of Quiruvilca are still further up the valley (to the left in the above photo – and the highway from Trujillo comes in from the right in the above photo). A mountain scene with the mill and company complex was visible from higher up the valley by the water tower, above and just beyond past the town and mine.

Town of Quiruvilca

The town of Quiruvilca packs a lot in – there isn’t much unused space.

Rocks are sometimes used to add extra weight to the roofing material.

We had a look around the central area – this little guy took a good look at us, but wasn’t inviting us for a drink.

Sunny breaks brought people outdoors again and the sun highlighted some of the colour in the streets.

Many of the structures and houses date back to earlier times in the life of the mining town.

The Quiruvilca Mine

The Quiruvilca Mine is an amazingly large complex of mining operations. Although mineralization was first discovered at Quiruvilca in 1789, commercial mining did not commence until the beginning of the 20th century. The mine has produced copper, gold, silver, lead and zinc – the latter three are key in the current operations. The workings consist of several different access adits leading underground to labyrinthine networks of tunnels, raises and stopes on many levels. These workings are so extensive, having been developed and worked continuously since 1907, that no-one was able to say for sure how many kilometres of workings there are underground. A guess from having been shown the maps and plans (including the areas that are now flooded) is that there could be between 100-200km of tunnels, and possibly even more.

Although working in these kinds of mines is dangerous, the company has rigid and extensive safety rules and regulations in place. When we arrived at Quiruvilca on our first night, we were immediately given a full session of safety training and testing – about two hours’ worth. We also had a visit that night with the company doctors for testing – which came in handy later for me when the altitude got me! These high altitude mines – particularly those with legacy workings like Quiruvilca – can be tricky places, and running one safely is a complicated business.

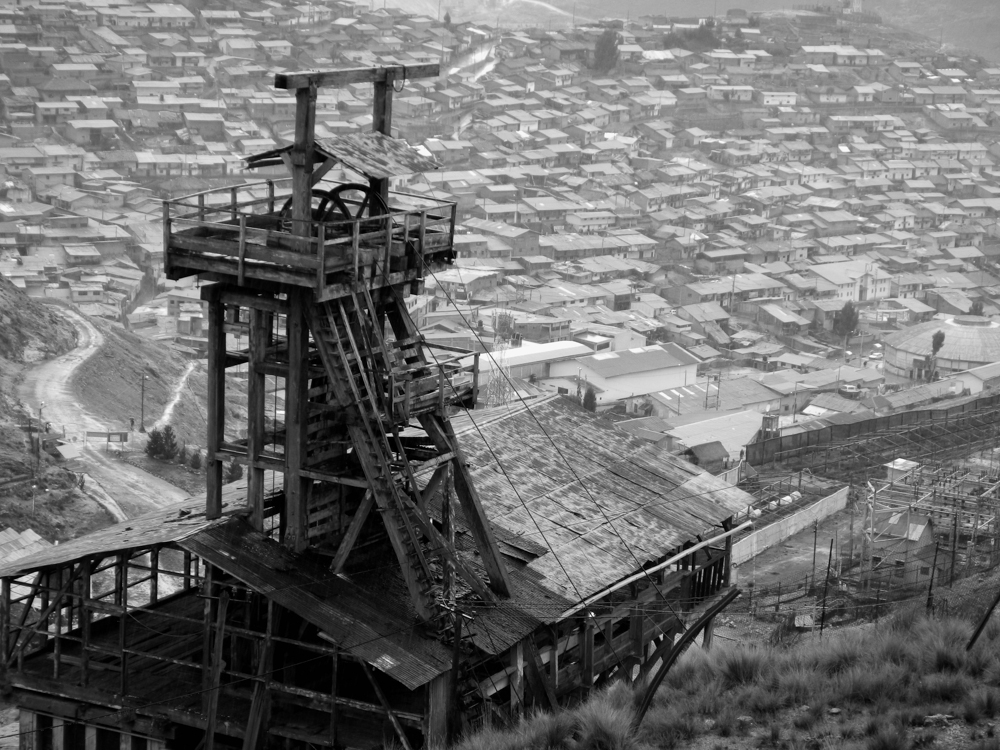

Part of the mine is serviced by the headframe over the Elvira shaft – the Pique Elvira. I thought I’d convey the feeling of being there in a black and white photo.

Today, mining at the Quiruvilca Mine involves small teams working stopes all over the workings – at any given time, approximately 60 separate stopes are producing and contributing to the ore going to the mill. When you think about it, this is an amazing amount of active development of headings at any given time! A total of nearly 1000 people work at the Quiruvilca mining/milling/office complex.

As for the mine itself, many of the tunnels are timbered, and some of them are constructed to accommodate rail cars to haul the ore.

The timbers are replaced every two years (water weakens them over time) and the rails are replaced approximately every 6 years.

Outside the adits, the ore cars are emptied – the photo below shows ore cars outside the Morrococha adit, with the Pique Elivira in the background on the hill.

Going Underground

We received detailed explanations of the workings from senior geologist, Edgar. Note all the timbers stacked on the right. We had the chance to visit a few zones in our time at Quiruvilca.

Underground, the tunnels and galleries are supported with timbers at various places – the walls are also bolted and caged in places. Some of the areas worked in the past are still visible from active areas. (Small note: you will notice bright spots in the underground photos – this is dust reflecting the flash on my camera – there is a lot of dust in the air underground when nearing active areas of the mine.)

After walking for perhaps 1.5km underground, we arrived at the raise – a series of ladders to be climbed to get to the working stope.

Up the ladders…

And at the top, we arrived at an actively working stope.

Significant amounts of woodwork have been put in place where the walls have little structural integrity – but even in these places it was possible to see minerals. The next photo below is a pocket that contained chalcopyrite and tetrahedrite – interesting, and some micro crystals but nothing that would be considered a fine mineral specimen.

We were taken to several working faces and given a chance to look for specimens. Senior geologists and supervisors joined in helping with our visit, and we could not have been given a better introduction to Quiruvilca.

Dave with senior geologist, Jose.

Between Dave and me is Mauro, senior supervisor in the Moroccocha workings, who led us up ladders into working stopes for collecting.

As mineral specimens go, being at Quiruvilca is similar to most mineral localities – you have to be in exactly the right place at exactly the right time, if you are to find fine specimens. If you stop and think about it, if the mine has 60 working faces operating for 365 days a year, the few specimens that you do see come from Quiruvilca each year come from all of that ongoing work. You would have to be in 60 places at the right time, every day, all year long, so that you were in the right place for the few fine specimens that are actually encountered. Doesn’t bode well for one’s chances on a short visit! (even though the company geologists did their best to take us to the places they felt would have the best chance on the days of the visit). We had a great time and found a few interesting small reference specimens, but that was all that was possible on this visit. We were able to examine the walls, collect what we found, and it was a super experience.

View of the sulfide veining at a working face.

As you can see, there aren’t exactly pockets gaping with crystals. In fact, the rock in the mineralized zones includes a lot of very soft material with poor competence – it just crumbles. As soon as the stope face has advanced, new timbers are put in place to support the walls. (Walking up the stope you simply climb over or under these.)

All along the stope, the sulfide-sulfosalt mineralization is evident.

Seeing lots of chalcopyrite-tetrahedrite veining, but sadly I’m not seeing any pockets or vugs here! (D.K. Joyce photo.)

Underground, we waited for the lift to return us up the shaft for the hike back out.

About that Altitude…

An elevation of 3800 metres may not sound that high. With no snow and no jagged peaks, it certainly didn’t look as if we were in thin air. But if you drive that whole ascent in a short few hours, and then dive into hiking with backpacks up and down mine ramps, and maybe add in a nice big dinner… I didn’t react that well. Two of my best friends at the mine were Miguel, the company doctor, and Mr. Oxygen Tank. Miguel grounded me from any collecting at all on Day 2 (bummer!) after I woke up in the middle of the overnight with crazy racing breathing (it was easier to breathe standing up than lying in bed (!)). They take the altitude issue very seriously – for example, once I mentioned to our house hostess Marina that I had had a small issue breathing overnight, an ambulance was at the house in under 2 minutes. And to go to the medical office for some oxygen that first morning, I felt I could easily walk, but that was refused – ambulance only. No chances are taken! With oxygen and some adjustment time, I was able to be more active after that, and was obviously more cautious, but for those of us who do not live at altitude, that rapid ascent is not for the faint of heart. Fortunately, Quiruvilca is a dry camp – had I had wine with that first dinner, I’m sure my issue would have been compounded.

Quiruvilca Geology

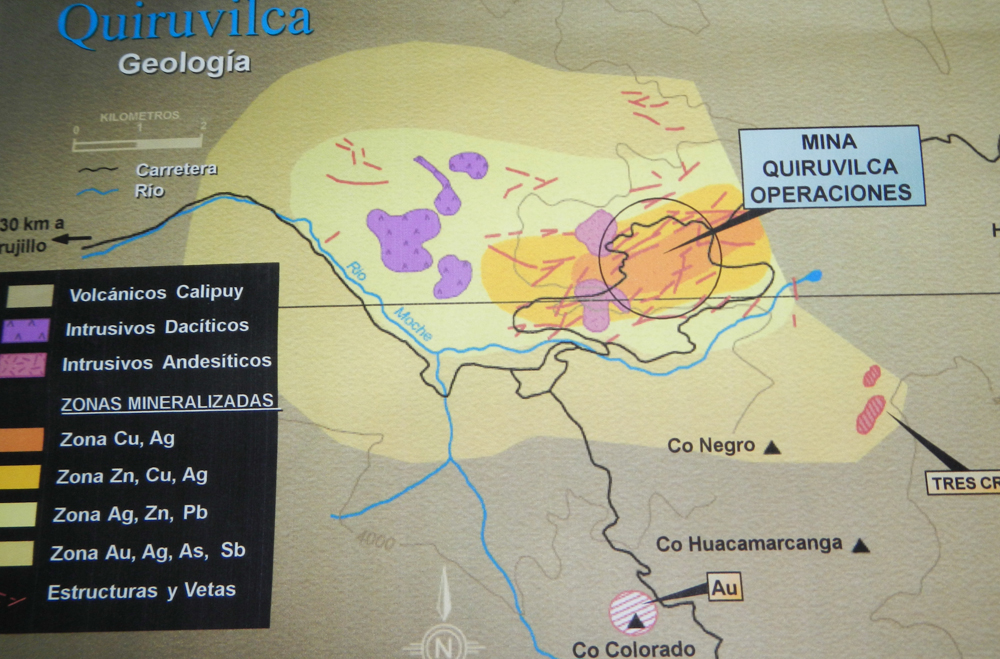

Excellent references include a discussion of the geology at Quiruvilca (see the list at the end of this post). As a basic overview, the geology is Miocene age – very recent in geological terms (the Miocene period is from approximately 23 to 5.3 million years ago). The host rocks are a mix of andesites, basalts and dacites, and the mineralization is concentrated in mesothermal and epithermal veins. The key to understanding the occurrence of the minerals at Quiruvilca is the classification of the four mineral zones, along with the occurrence of the vein structures.

The map below (provided by the company) gives an overview of the four zones – and note the veins (“vetas”) indicated as red lines.

The inner (orange) zone is referred to as the Enargite Zone. At one time, mining was concentrated entirely in this zone, and the workings here are extensive, though many are now flooded. This zone produced enargite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, galena, sphalerite, wurtzite, tennantite, the famous orpiment specimens, realgar, and the world’s best hutchinsonites. Sadly for mineral collectors, little mining is done here now, but some ramp work and development work have led to occasional interesting finds.

The next (deep yellow) zone, the Transition Zone, includes predominant sphalerite, with pyrite, tetrahedite-tennantite, chalcopyrite, galena, marcasite, arsenopyrite, covellite, seligmannite, jamesonite, quartz, calcite and rhodochrosite. Company records also indicate alabandite has been found in this zone.

The third (light yellow),the Lead-Zinc Zone, has been an area of high mining activity in recent times, in part due to the silver content. Mineralization includes galena, sphalerite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, tetrahedrite-tennantite, marcasite, jamesonite and arsenopyrite. Crowley, Currier and Szenics (1997) report gratonite and wurtzite from the Lead-Zinc Zone. Other minerals from this zone include quartz, calcite, dolomite and rhodochrosite. The company reports clinozoizite and manganaxinite from this zone.

Finally the outer (beige) zone is the Stibnite Zone, which is mostly beyond the area of the Quiruvilca Mine workings. Minerals of the Stibnite Zone include stibnite, arsenopyrite, arsenic, pyrite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite and galena.

Vein mineralization and paragenesis are discussed well in Crowley, Currier and Szenics (1997).

Quiruvilca Minerals

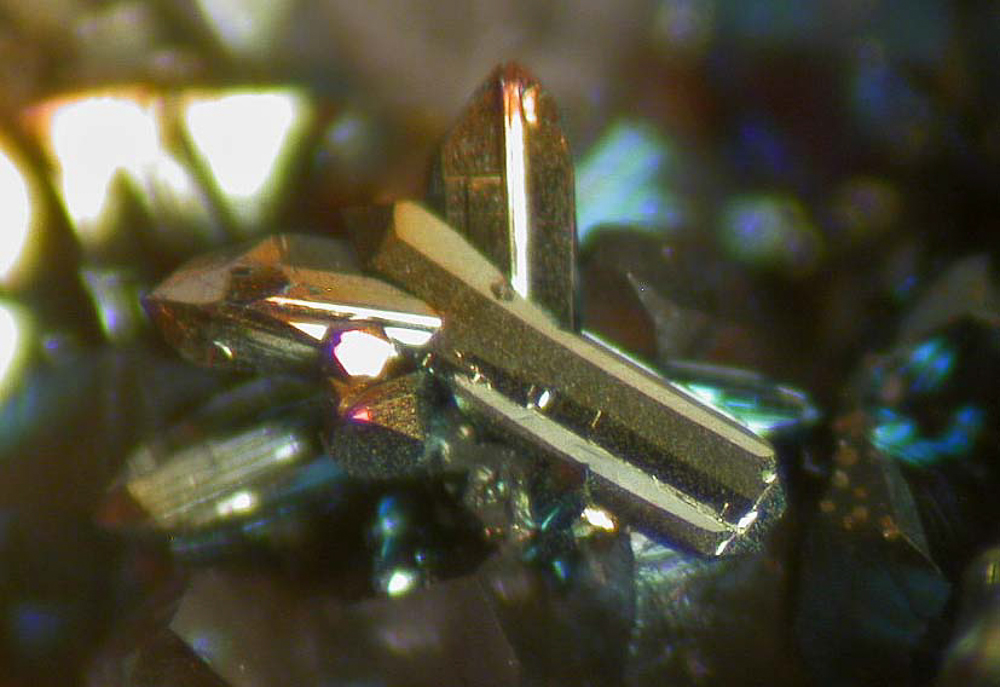

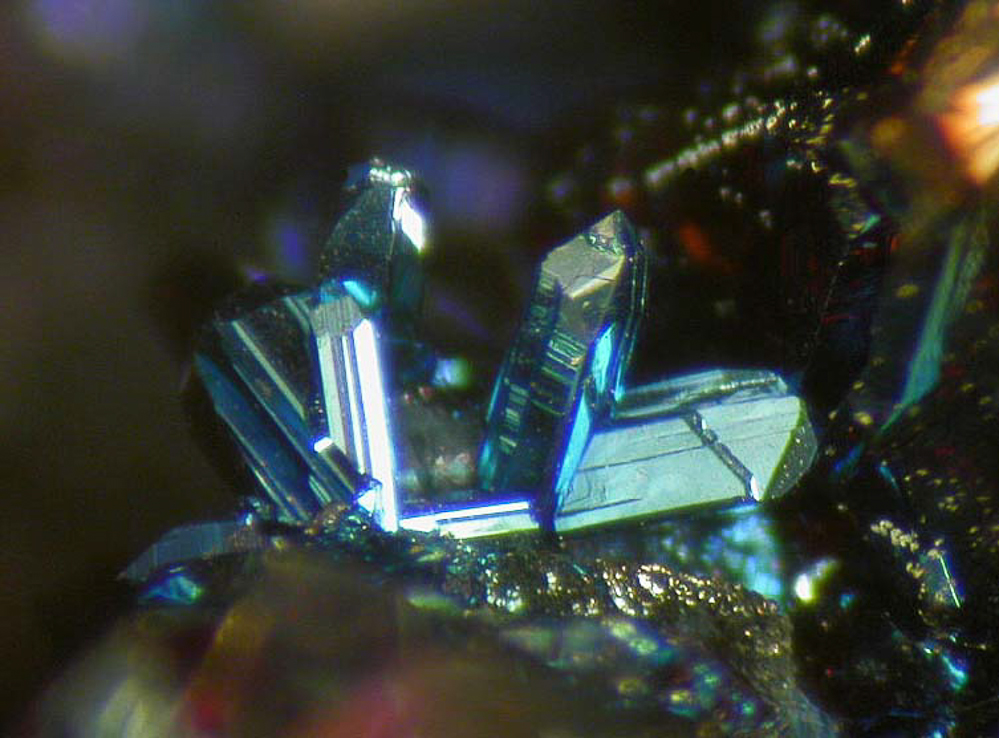

We did our best to procure minerals from Quiruvilca! Underground work did not result in anything spectacular, although on the day I was grounded with altitude sickness Dave found some pretty great seligmannites. These are microscopic crystals only, but they have great form and iridescent colour:

Seligmannite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Seligmannite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Seligmannite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Seligmannite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Seligmannite on sphalerite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Seligmannite on sphalerite. Field of view 1mm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

We tried to buy in Quiruvilca, but specimens were incredibly scarce. We knocked on doors at miners’ homes…

…mostly to no avail, but we came up with a few things…

…including a beautiful pyrite with octahedral crystal forms, totally overgrown by a second generation of pyritohedral crystals. 8cm across.

Most specimens make their way out of town within a short time of extraction from the mine – usually with runners who transport them ultimately to the mineral dealers in Lima. From there, many specimens go on to international mineral shows. One’s chances of intercepting fine mineral specimens at Quiruvilca itself are very low!

In any event, here are a few additional mineral specimens from Quiruvilca:

Arsenic – 10 cm

Enargite with pyrite – a great specimen from earlier mining days in the Enargite Zone – 8 cm

Bournonite crystals on quartz – 6 cm

Orpiment – 5.5 cm

Realgar crystals up to 1 cm on orpiment.

Wavellite balls (to 5 mm) on quartz, from recent mining.

Wavellite balls to 5 mm

Hutchinsonite 8 mm tall with orpiment. (D.K Joyce specimen and photo.)

Hutchinsonite 8 mm tall with orpiment. (D.K Joyce specimen and photo.)

Hutchinsonite crystals to 6 mm with tiny orpiment crystals.

Field of view approximately 3.8 cm.

Hutchinsonite with barite, orpiment and baumhauerite-2a, field of view 3 cm. (D.K. Joyce specimen and photo.)

Iridescent Sphalerite with micro Seligmannite and Quartz – Field of view 1 cm

Please note – the specimens photographed for this post are not available for sale on this website, but great Peruvian minerals are available here.

From Quiruvilca Along the Rio Moche Valley

We had a lucky break in the weather for our trip through the mountains and along the valley, so I thought I would end this post with some scenes from along the way.

Andes Mountains, from near Quiruvilca

Rural dwellings, near Quiruvilca

Rural dwellings, near Quiruvilca

Upper Rio Moche Valley (some limited farming along the valley)

Rio Moche Valley

Farms further down the valley

Picturesque small farm

Veranda in Otuzco (Might not hold party on this one)

Back to paved highway (thankfully!). Note traffic racing down middle of road.

Andes Mountains

Andes Mountains, with the clouds just beginning to move in

Thanks

First, of course, this could never have happened without an amazing effort organized by Adolfo and his team at Southern Peaks Mining. Thank you Adolfo! Thanks also to Pio, Edgar, Jose and Mauro for great geological, mineralogical, historical and technical insights. Thanks to Wilder, not only for all the driving around us Quiruvilca, but for dodging all those potholes on the road to and from Trujillo – and thanks to Marina for all the great meals. Special major thanks to Miguel and Mr. Oxygen Tank!

References

Excellent references for Quiruvilca and other Peruvian localities:

Crowley J.A., Currier, R.H. and Szenics T. (1997) Mines and Minerals of Peru. The Mineralogical Record. July-August, 1997, vol 28, no. 4.

Hyrsl, J, Crowley J.A., Currier, R.H. and Szenics T. (2010) Peru – Paradise of Minerals. Soregaroli, A. and Del Castillo, G., eds.

Hyrsl, J and Rosales, Z. (2003) “Peruvian Minerals: An Update” The Mineralogical Record. May-June 2003, vol 34, no.3.

Southern Peaks Mining website: www.southernpeaksmining.com