Categories

Archives

John and Merle White

It might seem unusual that I would begin by saying that John White and I are good friends… After all, this is the John S. White and there are many very important things to write about him. He is the former Curator-in-Charge of the U.S. National Mineral and Gem Collection, Smithsonian Institution, founder of the Mineralogical Record, author of two books and over 200 articles and hundreds of reviews and column contributions on mineral subjects, and consulting editor of Rocks & Minerals magazine and the Russian journal Mineralogical Almanac. His involvement in professional and amateur mineral groups has been extensive. The phosphate mineral whiteite is named after him. Through his professional achievements alone John has been one of the most active and influential mineral people of our time. At the same time, John’s friendships throughout the mineral world over the years have been not only important influences on the course of his own career, but they have been as important as any other impact he has had on the rest of us in our global mineral collecting community.

John at the Smithsonian, 2017

John, Paul Desautels and the Smithsonian

Going back to the early days of John’s story in the world of minerals, he became a mineral collector in 8th grade, when his teacher assigned each student the task of compiling a mineral collection. Imagine how different the world of minerals might look if not for that fateful day…

John was a mineral collector in his early teens, living near Baltimore. He learned at that time that Paul Desautels (who was to go on to become one of the most famous and influential mineral curators of all time) was teaching chemistry at Towson Teachers College (now Towson University), close to John’s home. One day John got on his bicycle, rode to the college, and introduced himself. This was the start of a great friendship in minerals and a connection that would impact so many of the things that would follow in John’s career.

Not long after becoming friends, John and Paul Desautels founded the Baltimore Mineral Society, and John met many prominent collectors from the US northeast through their meetings.

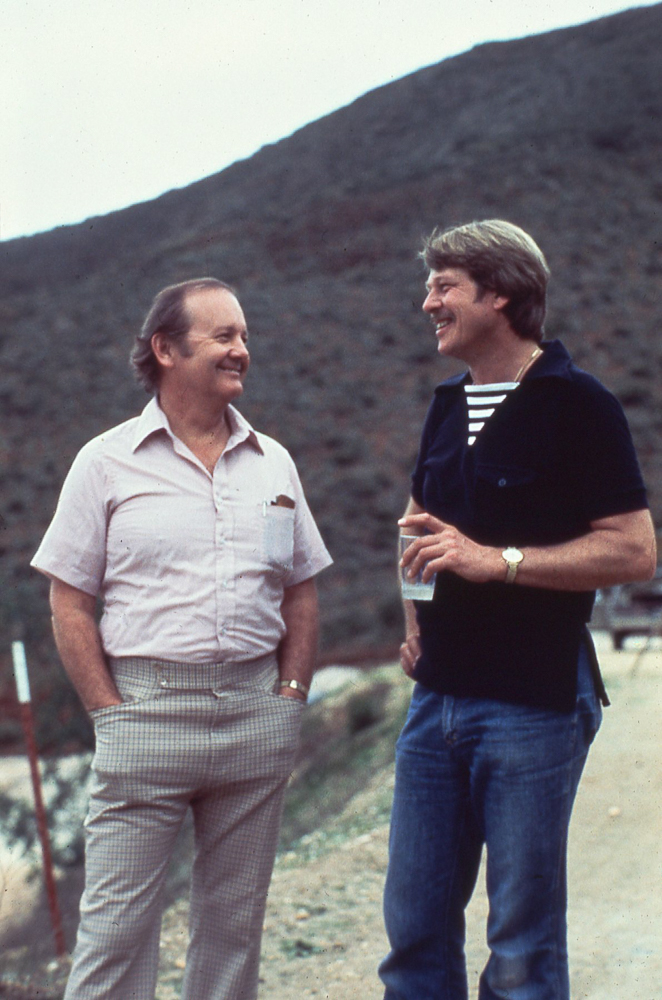

John with Paul Desautels

In 1957, Desautels was hired by the Smithsonian Institution as a curator in the Mineral Sciences Department. By this time the two friends had gone separate ways, as John had graduated in 1956, then served in the U.S. military in Germany for two years and moved out to Tucson where he completed his graduate studies at the University of Arizona in 1960. The two friends reconnected at several of the earliest Tucson mineral shows and three years later John received a letter from Desautels indicating that there was an opening for a technician in the Mineral Sciences Department at the Smithsonian. At the time John was working in field exploration for the American Smelting and Refining Co. (ASARCO), but with Desautels’ urging John applied for and was hired by the Smithsonian in 1963.

John’s described this development:

Working at the Smithsonian, the world’s greatest museum complex, and possessor of the world’s greatest public mineral collection, was of course a dream job. Not only was I immersed in a wealth of wonderful minerals, but I also had the opportunity to meet and develop friendships with most of the prominent mineralogists, private collectors and mineral dealers of the day, something that paid immeasurable dividends for me down the road. (White 2016).

John became curator in 1973 and was curator-in charge from 1984 to 1991, when he retired from the Smithsonian.

John at the Smithsonian, 1971

During his time at the Smithsonian John was involved with major acquisitions (including the famous Carl Bosch collection) and visits to famous finds at the time (the legendary find of the “blue-cap tourmaline” elbaite crystals at the Tourmaline Queen Mine in 1972, Pala Co., California, the big 1972 find of “watermelon tourmaline” elbaite crystals at the Dunton Mine near Newry, Maine), securing top specimens for the Smithsonian. Another classic US locality, the Foote Mine in North Carolina’s Kings Mountain Mining District, was the focus of much of John’s research. His work there contributed to the ongoing description of new minerals – the Foote Mine is the type locality for fifteen mineral species (!).

Equally important, throughout his career at the Smithsonian John developed friendships throughout the world of minerals, travelling all over Europe and North America, visiting collectors abroad and closer to home. Perhaps the most amazing of these experiences came in 1967, when the world famous mineral dealer, Martin Ehrmann, asked John to accompany him on a trip throughout Europe. Ehrmann had known that John had driven his 1950 Mercedes Benz all over Europe when stationed there with the US Army from 1957-58, and wanted to undertake the 5-week trip without having to do the driving.

John’s 1950 Mercedes Benz

So John drove around Europe on a 5,000 km journey to visit museums and collectors all over the continent… As he recalls it, “five weeks of driving the world’s best international mineral dealer around Europe was an absolutely amazing experience.” He has also described it as “the most fantastic experience a mineral lover could possibly have had.” (White 2016) Minerals aside, John enjoyed the opportunity to develop his friendship with Ehrmann and to meet so many mineral people throughout Europe.

How the Mineralogical Record was Founded

So… given that John’s career story so far was a rather full professional life, you might wonder how it was that John could possibly have founded the Mineralogical Record in 1970.

The publication of the Mineralogical Record from 1970 through the present has been one of the most important developments of all time for the advancement and sharing of mineral collecting knowledge. The founding of the magazine is one of the great stories in the mineral world. Of course, now, it is a leading publication we know and love, but it started with an idea and John’s will to see it through from humble beginnings.

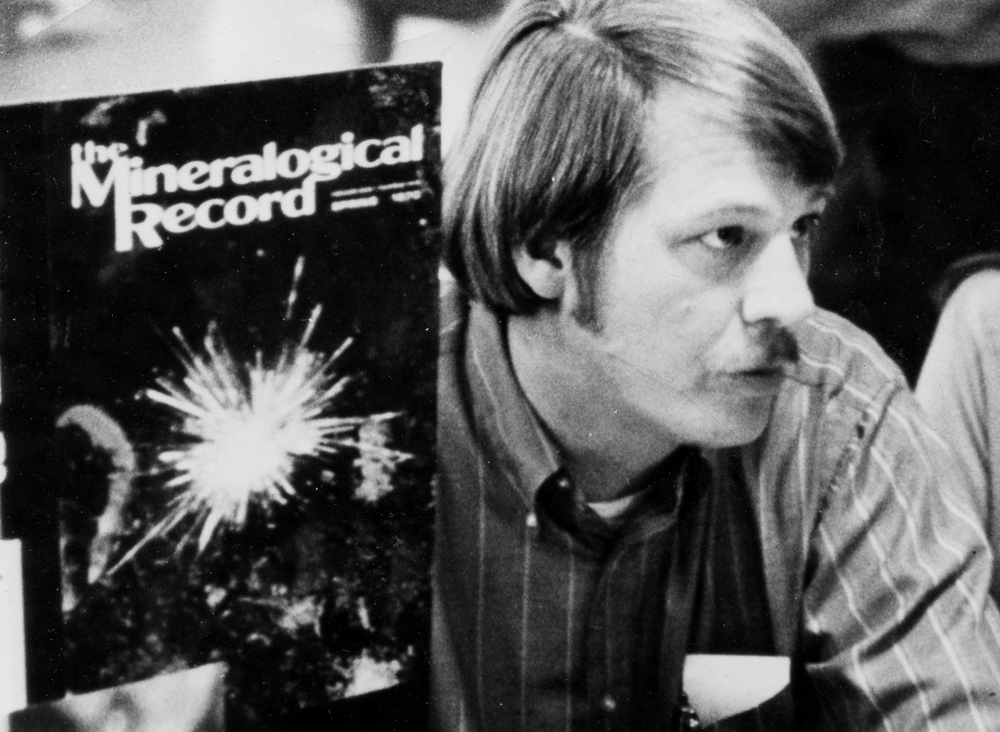

John with the first issue of the Mineralogical Record, 1970

John felt that in the late 1960s the state of the available mineral publications was quite poor. This is hard for us to imagine now because we live in what is truly a golden age for mineral writing and publishing. In English alone, the Mineralogical Record and Rocks and Minerals are superb magazines, the Lithographie monographs and books are fantastic, and many other books are as well. But in the late 60s such was not the case. Rock and Minerals was at that time a very different publication and John’s offers to assist the publishers in any role had been rebuffed. It was in this context that the idea for the Mineralogical Record had its genesis.

However, this was not the only reason the Mineralogical Record was born. John has described his “hidden motive,” and we are all lucky he had one. From his very first day as a technician at the Smithsonian Institution, it had been made clear to him that he could never become a curator there because he did not have a Ph.D. He had enrolled in a university program in Washington D.C. with the goal of completing a Ph.D., but he had been told by the Smithsonian Institution that even if he had a Ph.D. he would have to compete with many other highly-qualified applicants for a curatorial position. So, because John knew that a career as a technician would not be adequately satisfying, he decided to begin his own mineral journal in hopes that it would become significant enough to support him such that he would one day be able to leave the museum.

The rest of the story, in John’s words:

This resulted in the irony of ironies. After the first few issues of the Mineralogical Record were published, the director of the Natural History Museum was so impressed that he promoted me to a curatorship! Obviously, then it was no longer necessary for me to consider leaving the museum, and that was when the current editor, Wendell E. Wilson, started working with me… within a few years, he became the editor and took over most of the production responsibilities. (White 2016)

Even more ironically, following the 1981 developments at the Smithsonian Institution with Paul Desautels’ departure, the mineral department became the focus of increased scrutiny and sensitivity. John had continued to be involved with the Mineralogical Record and was still named in the magazine as its publisher, but auditors at the Smithsonian made the determination that his association with the Mineralogical Record posed too much appearance of conflict-of-interest for their comfort. As a result John was forced to cut all ties with the magazine and it was only in 1990 that his name reappeared in the magazine as “Founder.”

The Founding Days of the Mineralogical Record

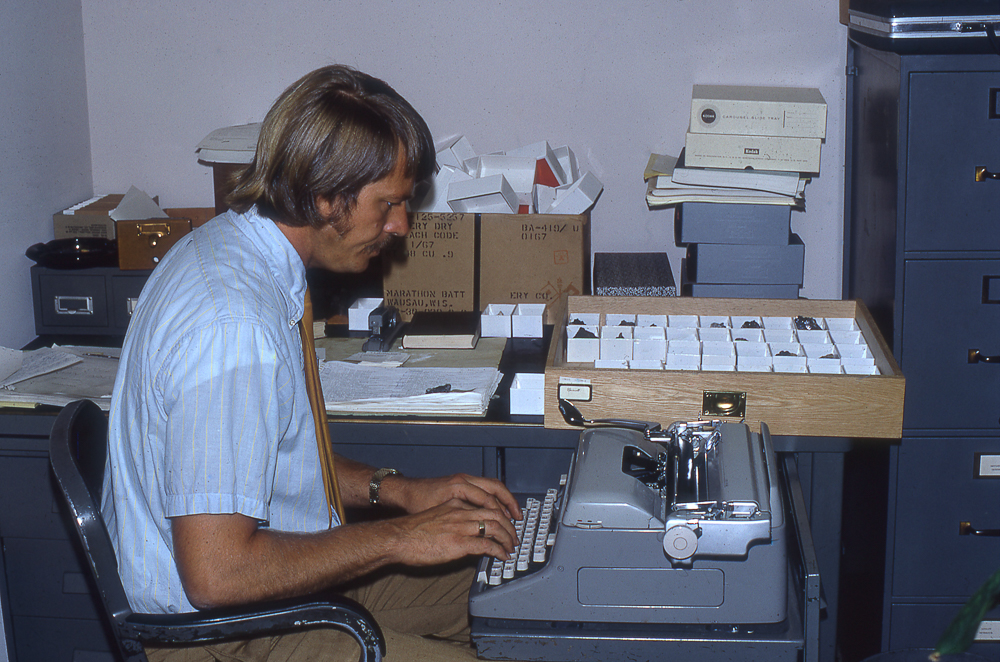

Now that the Mineralogical Record is the gorgeous glossy magazine it is today, it’s hard to imagine that John began it from scratch as he did. I agree with John that these days most of us almost take its existence for granted and we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about how easily it might never have been. Those early days involved many challenges for him – finding initial funding, managing all manner of actual production, from content to layout, from the practicalities of stuffing magazines in envelopes to adding subscribers and advertisers.

Every detail had to be worked through. For example… learning the hard way that some types of mailing envelopes were not up to the task of adequately protecting the magazines through the mail. So many details!

John credits the contributions of many people from this time – Paul Desautels provided “enthusiastic support,” Dr. Art Montgomery was fundamental to financing the publication, Richard Bideaux was instrumental in many ways, including bringing together the support of others. Peter Embrey was supportive and provided important input. At the same time, John himself was dedicating every minute imaginable to make the magazine reality.

In John’s words:

A complication that had to be worked out early on was arranging to get together with representatives from the graphics company without imposing on my work schedule at the museum. Happily, we found it was sometimes possible for them to bring materials to my home in the evening or meet with me over lunch. In the latter case this usually involved my speeding off in my car at noon, grabbing a snack at a fast food place along the way, munching my lunch over the layouts and bluelines in the office of the graphics company, then racing back in order not to have been gone longer than an hour. Fortunately their office was no more than a few miles from mine. Color separations for the covers were usually passed to me in the parking lot of the museum, where I could stash them in the trunk of my car to study them later at home. Evenings and weekends were totally consumed with soliciting articles, editing manuscripts, proofing copy and handling a great variety of correspondence, especially those relating to advertising (White 1995).

Of course, aside from the logistics and practicalities, there was the content of the Mineralogical Record – the work of an editor, along with the writing of editorials, abstracts for new mineral notes, and the early columns of what’s new in minerals. John managed this while he also did his best to balance his growing family, with three young daughters. The first issue of Mineralogical Record was mailed on the first Thursday of June, 1970, and the rest is history.

Rocks & Minerals Magazine

John has always enjoyed working to improve mineral literature, and over the years after the Smithsonian he became an increasingly involved contributor to Rocks & Minerals magazine, for which he is on the editorial board. He has written a great column, “Let’s Get it Right,” focusing generally on resolving vague or misused concepts, identifications or other information about minerals, correcting common inaccuracies, in current usage, and so on. As a retired lawyer, I love accuracy of language and I have enjoyed many discussions with John about such things.

As a fun aside, there is an example of non-mineral language where John and I have been unable to agree. I used to use it in mineral descriptions on the website, and every time I’d do it, John would send me an email critique. I no longer use it in mineral descriptions. In Canada, it is very common to colloquially use the phrase “these ones.” As in, “Oh, I really like these ones!” Or, in the case of specimens from a particular find, “These ones have particularly good colour and lustre.” It’s an informal usage one hears all the time up here in the Great White North. Well, John feels strongly that this is incorrect usage and we have an impasse. Although… I recently stopped him as he said “this one” and asked why that would be ok if “these ones” is not. I’m still hoping for an answer that might have some merit…

But I digress. John has also written excellent, helpful articles in Rocks & Minerals under his periodic column “Mineral Mysteries,” addressing curious mineralogical phenomena which need further analysis or explanation. My favourite two of these are “Crystal Faces on Etched Crystals” and “Quartz Cores in Tourmaline Crystals” (full references below) – reading each of these was a true mineralogical “Eureka!-moment” for me.

John’s Mineral Collection

John began collecting minerals at an early age – his love of minerals has been a part of his life since that fateful grade 8 assignment.

From his early collecting days John has always had a fondness for the minerals of his region of the United States – Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. One of John’s greatest collecting experiences in those times was at the Fairfax Quarry, Centreville, Virginia, where he and a friend opened a large pocket of classic green prehnite with hydroxyapophyllite.

Hydroxyapophyllite, Prehnite, Fairfax Quarry, Centreville, Fairfax Co., Virginia, USA – 15.1 cm

NB: This specimen was not personally collected by John – it was in his collection, from the Jim and Dawn Minette collection.

Over the years, John has been involved in field collecting at some rather famous localities. In his Arizona days, he collected at many localities including the Glove Mine, the Rowley Mine and Washington Camp. He has collected in Europe as well, and most recently he has collected closer to home, including at the classic limestone quarries at York, Pennsylvania and the relatively recent workings for beautiful smoky quartz in Schuylkill Co., Pennsylvania.

Today John’s collection includes great mineral specimens from around the world. He has particular interests represented by suites within the collection: (1) The minerals of Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland and Delaware; (2) Quartz; and the two related sub-collections, (3) Single Crystals and (4) Twins (i.e. in these latter two, all specimens are crystals only, no matrix). These latter suites were featured in the Mineralogical Record (Moore 2009), although they have evolved rather significantly since that article was written.

When John gave a talk on his single-crystal collection at the Rochester Mineralogical Symposium in 2018, he recalled the moment that hooked him on crystals. On one of his early visits with Paul Desautels at Towson Teachers College, John was looking through mineral specimens in a chemistry lab drawer when he picked up and gazed into a beautiful greenish-yellow crystal of fluorapatite from the classic locality Cerro Mercado, Durango, Mexico. That was it: he was a goner. That crystal sparked a lifelong fascination that has actually impacted a lot of people…

The single crystal and twin collections include many specimens that approach the idealized crystal forms illustrated so often in texts, and many of the most straightforward forms are reminiscent of antique wooden crystal models.

Carrollite, Kamoya South II Mine, Kamoya, Kambove District, Katanga,

Democratic Republic of the Congo – 2.4 cm

Friendships

John has credited the course of his professional life to “remarkable serendipity,” “coincidences” and “extreme good fortune”. And sure, there were good moments along the way, as we all have. But there’s clearly a lot more to it. Talent, knowledge and clearly lots of hard work are also part of it. And more still, John has developed friendships throughout the mineral collecting community all around the world, going back to his youth. It would be total folly to try to list those here, but going back to his friendship with Paul Desautels and all that followed after… John has had good friendships with so many mineral collectors and mineral professionals across generations.

Friends at the Rochester Mineralogical Symposium, 1979, after all of whom minerals have been named:

Front (L to R) – Prosper J. Williams, Paul B. Moore, Peter G. Embrey

Middle (L to R) – Richard V. Gaines, John S. White, William W. Pinch, Charles L. Key, Hatfield Goudy

Back (L to R): Richard A. Bideaux, Paul E. Desautels, Joseph A. Mandarino, Louis Perloff,

John B. Jago (Trelawney), Robert W. Whitmore, Robert I. Gait

These friendships made possible many of John’s mineral experiences and contributions, and have included great shared mineral moments around the world. Including this part of the world…

John working a calcite vein dike with me and George Thompson near Tory Hill, Ontario.

Try walking anywhere together with John at a major mineral show – the greetings come from left and right and it can take a while to actually get anywhere.

And finally just a warning. John is sometimes still The Editor at heart. Even over a drink or dinner, you slip up grammatically or mineralogically, and you do so at your own peril…

P.S. If you’ve landed on this article via the Profiles and Tributes section, you may have noticed that it’s a relatively newer section on the website, with only one other tribute at the time of writing this – the tribute to Emery, our beloved lab. You might have wondered what John thinks of being side-by-side with a dog… If so, you’ll be happy to hear that John loves their dogs, past and present, as much as we love ours, and knows that there is no higher honour from me than to be in a column side by side with Emery!

John and Scooter

—-

Thanks to John for all of the older photos from his collection.

References

Moore, T. Collector Profile: John S. White, Jr. and his Single Crystal Collection. Mineralogical Record 2009 40:3, 215.

White, J. S. For the Record: How the Mineralogical Record Came to Be. Matrix. Winter 1995, 115.

White, J. S. The Early History of the Mineralogical Record. Mineralogical Record 2004 35:1, 73.

White, J.S. Mineral Mysteries: Quartz Cores in Tourmaline Crystals. Rocks & Minerals 2015 90:5, 462.

White, J. S. Reminiscences of a Very Old Former Curator. Mineralogical Almanac 2016 21:1, 44.

White, J.S. Mineral Mysteries: Crystal Faces on Etched Crystals. Rocks & Minerals 2016 91:5, 459.

Wilson, W.E. John S. White. Mineralogical Record Biographical Archive, at www.mineralogicalrecord.com. Accessed July 17, 2019.