Categories

Archives

Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy has been famous among mineral collectors for a long time. In fact, these coastal cliffs were internationally-known for their zeolites before Canada existed as a country.

(Just a note: this post is really The Bay of Fundy Part I. The next post, Part II, is about collecting the Islands, in the Bay of Fundy, so I hope you’ll find that one fun too – the link is below, under the Links heading near the end of this post.)

Early summer morning at Wasson’s Bluff

Early summer morning at Wasson’s Bluff

Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy shoreline occurrences are early classic Canadian mineral localities, and have been producing superb specimens of many mineral species since the mid-19th century. For perspective, this is well ahead of the recovery of mineral specimens from other well-known Canadian localities like the Jeffrey Quarry at Asbestos or Mont St. Hilaire (Quebec), the Bancroft Area or Thunder Bay District (Ontario) or Rapid Creek (Yukon) – in some cases, over 100 years before the minerals of these localities were even discovered.

Specimens from the Bay of Fundy were noted in late 19th century texts and reports in Canada and internationally, and crystals of of gmelinite from Pinnacle Island (albeit as “Pinnack Island”) are included in Victor Goldschmidt’s early 20th century Atlas der Krystallformen.

Today, fine mineral specimens are still periodically recovered along the coasts of the Bay of Fundy, making this area one of the most productive contemporary regions for Canadian fine mineral specimens.

This post focuses on three classic localities: Wasson’s Bulff, Amethyst Cove and Cap D’Or. Part 2, a second post, is about two more classic localities, Two Islands and Five Islands – a link is at the end of this post.

Geography

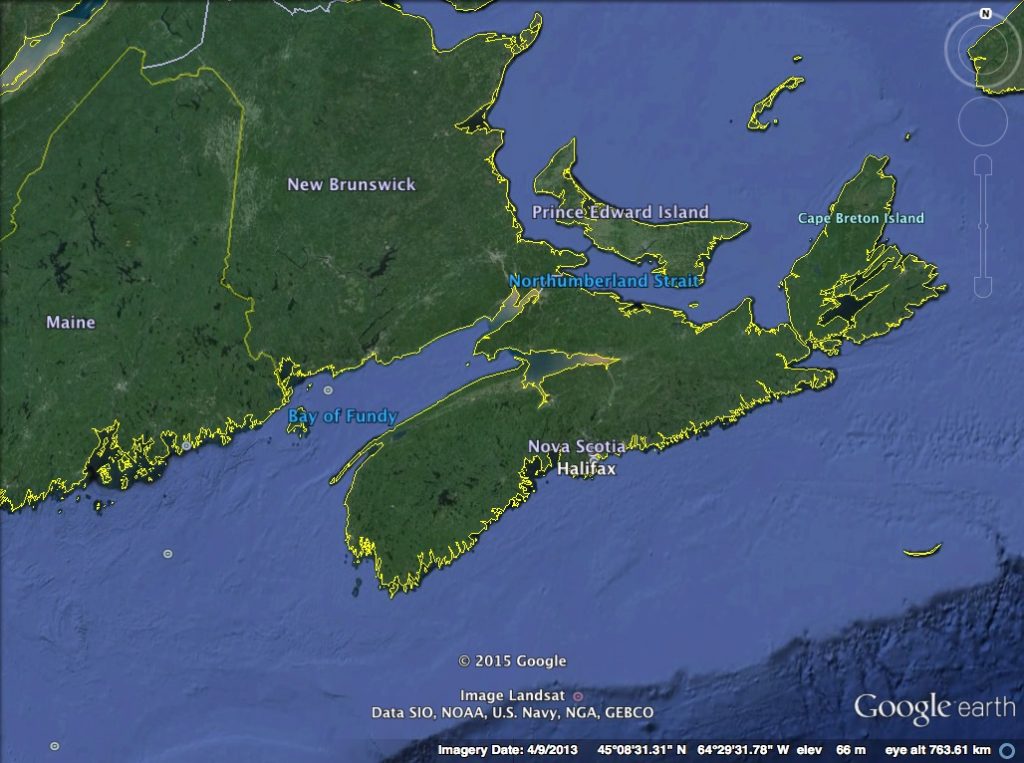

First, just a bit of orientation. As shown to the left of centre on the map below, the Bay of Fundy is a large, elongated bay on the Atlantic Ocean. The area of interest for mineral collectors is at the northeastern area of the Bay of Fundy, including the Minas Basin, in the centre of the map. From Cap D’Or on the north shoreline, to the Morden area on the south shore, the linear length of shoreline to travel to the various mineral occurrences is over 400 km (approximately 250 miles).

Note in particular the tiny hook-shaped feature (the Blomidon Peninsula) poking up in the middle of this map, separating the triangle-shaped Minas Basin from the wider Bay of Fundy.

(Google Earth 2015, Image credits: Landsat, NOAA.)

(Google Earth 2015, Image credits: Landsat, NOAA.)

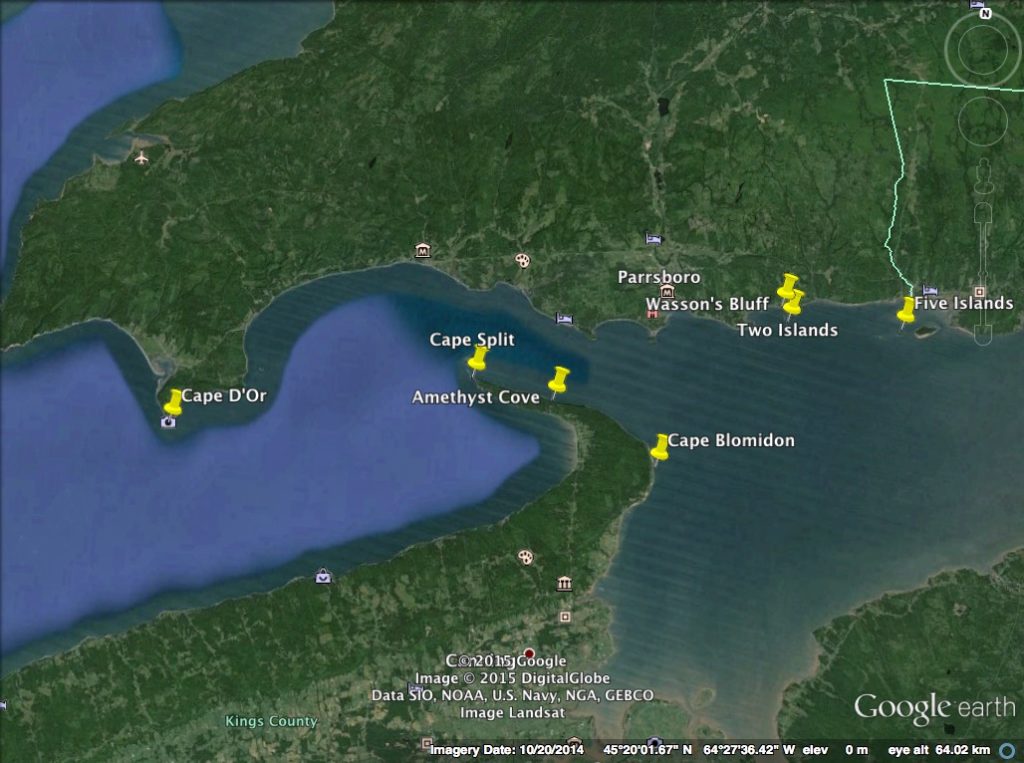

Zooming in closer, with the “hook” of the Blomidon Peninsula in the centre of the map below, I’ve plotted just a few of the most important Bay of Fundy mineral localities. These are to give a general idea, but in many cases the names of localities on the Bay of Fundy are used to refer to a stretch of shoreline, not one specific plotted point. The town of Parrsboro, right of centre, hosts the Nova Scotia Gem and Mineral Show every August (a long-established show, it has passed its 50th anniversary), and is home to the Fundy Geological Museum.

(Google Earth 2015, Image credits: Landsat, NOAA.)

(Google Earth 2015, Image credits: Landsat, NOAA.)

In this post, I use the term “Bay of Fundy” to include the area that is known as the Minas Basin, east of the Blomidon Peninsula.

Background – World Class Mineral Specimens

From the 1830s on, the Bay of Fundy began to attract attention for its mineral occurrences, particularly the zeolites and associated minerals.

Several minerals occur in world-class specimens from the Bay of Fundy localities: analcime, chabazite and gmelinite are the classics.

Excellent specimens of natrolite and thomsonite are also found. Even certain more common minerals, known in spectacular specimens from other world localities, occur in rather unique specimens from the Bay of Fundy – for example, stilbite colours range into distinctive and beautiful golden yellow and cinnamon brown, while heulandite can be various colours, including brilliant orange. The type locality for mordenite is Morden, on the south shore of the Bay of Fundy.

It should be noted that the Bay of Fundy is also known for agates and pretty amethyst specimens.

About the Bay of Fundy

The coastlines along the Bay of Fundy include many exposures of rock, including cliffs up to about 100m (300 ft) high. The Bay of Fundy mineral localities are typically exposed rock the base of the cliffs themselves, and also some large rock falls where cliff sections have collapsed onto the beaches.

Sunrise from camp at the top of the Cape Blomidon cliffs

Sunrise from camp at the top of the Cape Blomidon cliffs

Unlike many other mineral localities, the Bay of Fundy occurrences are constantly refreshed by strong forces of nature. The Bay of Fundy itself does a lot of the work. The ocean here is particularly powerful, with incredible tides, periodic major Atlantic storms and occasional hurricanes.

The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world: the difference between high and low tide can be about 16 metres (over 50 feet) (!).

Long way down to the boats at low tide on the Bay of Fundy

Long way down to the boats at low tide on the Bay of Fundy

The waves and the pounding action of the tides, compounded by storms, scour the shorelines. Of course they also have the power to pile lots of unwanted rock on top of a good vein and bury it – so one never really knows what to expect at a locality on any given visit! The cliffs themselves are highly susceptible to erosion from heavy rain storms, and particularly from the freeze-thaw cycle in winter. Huge sections of the cliff walls crash down onto the beaches, and sometimes those rockfalls contain excellent mineralized zones.

All this action from the ocean is helpful, but it is also a power to be respected, both on the water and on the shore. From low tide to high tide, 14 cubic kilometres (14 billion tonnes) of water race through the relatively narrow gap between Cape Split and Cap D’Or. It is said that during a rising tide, at mid-tide, the channel by Cape Spilt is filled at a rate of 4 cubic kilometres of water per hour, equal to the combined flow of all of the world’s rivers and streams. This causes turbulent tidal currents and can create treacherous boating conditions.

Lighthouses have dotted the Bay of Fundy clifftops since historical times.

Lighthouses have dotted the Bay of Fundy clifftops since historical times.

The ocean looks pretty peaceful from this high up on the cliffs…

It goes without saying that one needs to be very careful when collecting along the Bay of Fundy. (Please read the Please Use Caution section at the end of this post.) Collecting trips are timed exactly with the tides – at some locations, getting caught on the shore against the cliffs in a rising tide would be fatal. In addition, one must be careful about being anywhere near the cliffs, and obviously hard hats are worn in these areas. True, with the rare rockfalls that exceed the size of a car, the hard hat would be about as useful as Wyle E. Coyote’s umbrella, but most of the time what falls is small enough that a hard hat can save you a nasty headache, or save your head from becoming cratered.

Overview – Geology

The geology of the cliffs and surrounding Bay of Fundy formations reveals a complex history, far beyond the scope of this post. The rock formations exposed in this region include Carboniferous, Triassic and Jurassic deposits. Various rock types outcrop in the cliffs, including basalts, sandstones and siltstones. Many of the sedimentary rocks in the Bay of Fundy host important fossil occurrences, notably the early reptile fossils in the outcrops at Joggins, and dinosaur fossils in the sandstones near Parrsboro and Wasson’s Bluff.

Cliff section exposing basalt and sandstone at Wasson’s Bluff

Cliff section exposing basalt and sandstone at Wasson’s Bluff

Of greatest interest to mineral collectors are the basalt exposures. These relate to many separate lava flows during the late Triassic period (a little over 200 million years ago) and they host cavities and vein structures in which well-crystallized minerals are found. The cavities, known as amygdules, were originally formed as gas bubbles trapped in the lava as it cooled and hardened. Later, water flooded the amygdules and minerals formed. (Among the most commonly seen examples of amygdules from basaltic-host environments are the large amethyst cavities from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, and Artigas, Uruguay).

Small amygdules containing zeolite minerals in fractured basalt at Amethyst Cove.

Small amygdules containing zeolite minerals in fractured basalt at Amethyst Cove.

Within the Bay of Fundy deposits, in addition to the amygdaloidal basalt occurrences there are significant breccia zones, where fluids filled cracks and mineralized veins resulted. Most often, as in the photo below, these are narrow seams with minimal potential for mineral specimens, but some of these veins are of sufficient size and complexity that they include excellent hollow zones and cavities in which crystals formed. Crystal-hosting zones are often very narrow and must be collected with extreme care, while it is very common to see crystals that just didn’t have adequate open space to fully develop. Certain seams have allowed for the development of crystallized copper.

Typical breccia zone seam containing small chabazite crystals on the beach at Wasson’s Bluff

Collecting Minerals Along the Bay of Fundy

At some localities along the Bay of Fundy, collecting is not for the faint of heart (figuratively or literally).

As one might expect, access is over the cliffs, down to the shores. In places, ropes are needed.

Grab on and down we go! A small section of the ropes on the trail to Amethyst Cove.

Grab on and down we go! A small section of the ropes on the trail to Amethyst Cove.

Over the last clifftops and down, at Cap D’Or

Over the last clifftops and down, at Cap D’Or

Wasson’s Bluff

Of course it’s hard to isolate a single Bay of Fundy locality, but if one had to choose, perhaps the most prolific one through mineral collecting history has been Wasson’s Bluff, which has been collected since the mid-nineteenth century.

The view at Wasson’s Bluff (which is along the shore).

The view at Wasson’s Bluff (which is along the shore).

This scene is looking toward Two Islands and Five Islands, at nearly high tide.

Wasson’s Bluff is known for superb chabazite crystals, balls of natrolite crystals, analcime crystals and golden-yellow stilbite fans.

It should be noted that Wasson’s Bluff has a protected designation under provincial law. Collecting is only permitted on the beach, and not in the cliffs. (All specimens depicted herein were obtained legally.) It is also important to observe that some of the access requires the crossing of private land and permission must be obtained.

One can access Wasson’s Bluff via different routes. One of them follows a narrow gully carved in the sandstone by runoff waters.

George Thompson and David K. Joyce making their way down to Wasson’s Bluff

George Thompson and David K. Joyce making their way down to Wasson’s Bluff

David Joyce took this photo of me descending the rope through the gap in the cliffs.

David Joyce took this photo of me descending the rope through the gap in the cliffs.

(Note the background expanse of the tidal flats at low tide. At high tide, the water is up at the driftwood by the cliffs.)

The name Wasson’s Bluff is used to refer to a fairly long stretch of shoreline cliffs, rather than a single cliff or outcrop.

A late spring scene at Wasson’s Bluff, tide receding

A late spring scene at Wasson’s Bluff, tide receding

Some good collecting can be done when cliff sections have come down onto the beach as rock falls. A current one is the “Analcime Fall”, where lustrous glassy analcime crystals can be found.

The collapsed cliff section at Wasson’s Bluff known as the “Analcime Fall”. (Two Islands on the horizon).

The collapsed cliff section at Wasson’s Bluff known as the “Analcime Fall”. (Two Islands on the horizon).

I use the term “current” for the Analcime Fall because even though it is large, just as with everything else on the Bay of Fundy, the ocean will devour this rock pile.

Other mineralized zones outcrop when the tidal waters have scoured the beach clear, making beach collecting possible. For example, in the zones known to host chabazite crystals, some veins and vugs are exposed in the rocks down on the beach. These openings are often very tight, interconnected cavities with little open space for the crystals to have developed. The intergrown crystals are fragile and the basalt is friable, making these very difficult to collect as fine mineral specimens.

Chabazite in this vug had particularly fine deep orange colour and good lustre.

Chabazite in this vug had particularly fine deep orange colour and good lustre.

This is in situ on the beach at Wasson’s Bluff and the largest crystal is about 2 cm.

Sadly, the largest crystal in the above photo was cracked, as you can see if you look closely. However, the next photo shows a fine specimen that was successfully collected from the vug above:

Chabazite with Heulandite and Calcite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 7.2 cm

After a good day on the beach, there are specimens to haul back.

Returning along the beach at Wasson’s Bluff. David Joyce photo.

Here are some specimens from this classic locality:

Natrolite on Analcime, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 2 cm crystal ball

Natrolite on Analcime, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 2 cm crystal ball

Natrolite on Analcime, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – crystal ball 2 cm

Natrolite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 5.7 cm

Natrolite on Analcime, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – balls to 1.1 cm

Natrolite with Analcime, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia

Field of view approximately 5 cm

Chabazite with Heulandite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 3.0 cm

Twinned Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – crystal 1.1 cm

Chabazite (beautifully twinned), Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 3.0 cm

Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 7.7 cm

Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 7.7 cm

An interesting note about Wasson’s Bluff chabazite, as we’re strolling through some of the various chabazite colours from the locality… At one time, the dark brick-red crystals (such as in the photo below) were given the mineral name “acadialite”, after Acadia, the name (L’Acadie) of the French colony that was comprised of modern-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and parts of eastern Quebec and Maine. However, when it was ultimately determined that there was no composition distinction between acadialite and chabazite, acadialite was dropped and is now an obsolete name for chabazite. One still sees the name acadialite on old labels once in a while.

Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – crystals to 2.0 cm

Stilbite with Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia

Field of view approximately 4.5 cm

Stilbite on Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia

Stilbite on Chabazite, Wasson’s Bluff, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia

Field of view approximately 2.5 cm

Even though the arrival of fall in Canada is a sad signal that we’re almost done collecting until spring, we nonetheless appreciate that the woods above Wasson’s Bluff are beautiful in the fall!

Birch, maple and fir in the woods above Wasson’s Bluff.

Birch, maple and fir in the woods above Wasson’s Bluff.

Amethyst Cove

Amethyst Cove is one of the well-known localities on the Blomidon Peninsula, between Cape Blomidon and Cape Split. The mineral locality name “Amethyst Cove” is usually used to refer to a significant stretch of the coastline between Cape Blomidon and Cape Split, and not only the cove itself.

Collecting at Amethyst Cove presents a more significant expedition than most other localities on the Bay of Fundy. The hike is a bit involved, with forest sections, rocky beach sections, and of course the ropes. Lots of ropes.

A nice gentle start greets you at the top of the rope section.

But the fact that the Minas Basin is so far below, visible looking down through the trees…

… means that this is what I think of when I think of Amethyst Cove.

Terry Collett down on the next ledge, undoubtedly wondering what’s taking me so long. He flies over terrain like this.

Terry Collett down on the next ledge, undoubtedly wondering what’s taking me so long. He flies over terrain like this.

Down at the base of the cliffs, the scenery is stunning.

The shoreline hike to Amethyst Cove (which is out near the point)

The shoreline hike to Amethyst Cove (which is out near the point)

David Joyce exploring the seams at Amethyst Cove

David Joyce exploring the seams at Amethyst Cove

As the name would suggest, Amethyst Cove has long been known for vugs of amethyst crystals. Often a mid-purple colour, most frequently the vugs and crystals are relatively small (comparatively speaking, in relation to world localities). They are quite distinctive and attractive, often with pale agate in association. Amethyst Cove and the Blomidon Peninsula host seams of agate of various kinds, and people hike the beach searching for them. The colours and aspects of these agates vary considerably (and it’s beyond my field of experience in general) – here is a typical one from Big Eddy.

Agate and Quartz, Big Eddy, Blomidon Peninsula, Kings Co., Nova Scotia – 8.8 cm

However, among mineral collectors, the true classics for which Cape Blomidon and Amethyst Cove are best known are the analcime crystals. The finest analcime crystals from here rank among some of the finest from anywhere.

Analcime with Stilbite, Amethyst Cove, Kings Co., Nova Scotia – 3.3 cm crystal

Analcime with Stilbite, Amethyst Cove, Kings Co., Nova Scotia – 1.3 cm crystal

Cape Blomidon has also produced excellent specimens of thomsonite (thomsonite-Ca) in mounds and balls of small bladed crystals.

Thomsonite, Cape Blomidon, Kings Co., Nova Scotia

Field of view 1.5 cm

A pocket opened up by David Joyce at Amethyst Cove in 2015 produced a few crystals of apophyllite that are quite large for this species along the Bay of Fundy.

Apophyllite, Amethyst Cove, Kings Co., Nova Scotia – 4.4 cm crystal

One absolutely great thing about ropes and cliffs… is that they make you think long and hard about how much rock you really want to haul out from the site. (You already have your equipment weighing down your pack…)

David Joyce and Terry Collett on the ropes as we start back up

As soon as you get to the top of one section, you have a nice clear view of… the next section. Up, up, up!

Cap D’Or

Back on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy, Cap D’Or is spectacular, both for its cliffs and its minerals. The hike to Cap D’Or is moderate, with ropes to assist, but the route is not as steep or as long as Amethyst Cove. The last stretch down the rock face at the shore can be done by rope down the small waterfall, or by ladder. Down at the shore, the rugged cliffs stretch on in either direction.

The Cap D’Or cliffs are huge. In the following photo, Terry Collett gives a sense of scale, at the small bottom section of one of the large cliff walls.

Terry Collett examines a zone that has produced mesolite, stilbite and other minerals in the past

Terry Collett examines a zone that has produced mesolite, stilbite and other minerals in the past

Everything at Cap D’Or seems large – the boulders and rocks on the shoreline require a bit of careful navigation if you want to make any progress (and remain upright!)

David Joyce took this photo of me for scale

David Joyce took this photo of me for scale

Some of the pocket zones along this shoreline are impressive.

David Joyce in a mesolite pocket zone

David Joyce in a mesolite pocket zone

Earlier in 2015, a large wall section came down from high on the cliff face, and crashed onto the beach – it is full of mineralized cavities and seams. Shown in the photo below, this is an example of a rock fall where neither your hard hat nor Wyle E. Coyote’s umbrella would save you.

George Thompson and David Joyce examining vugs and seams

This fall was informally named the “Apophyllite Fall”, as it yielded large numbers of specimens hosting sharp colourless apophyllite crystals. The rocks in this fall zone also contained significant amounts of mesolite and some associated stilbite. (The mesolite we found exposed at surface was cool to see, but not fine mineral specimen-calibre).

Mesolite covering a cavity wall – field of view approx 10 cm.

Mesolite covering a cavity wall – field of view approx 10 cm.

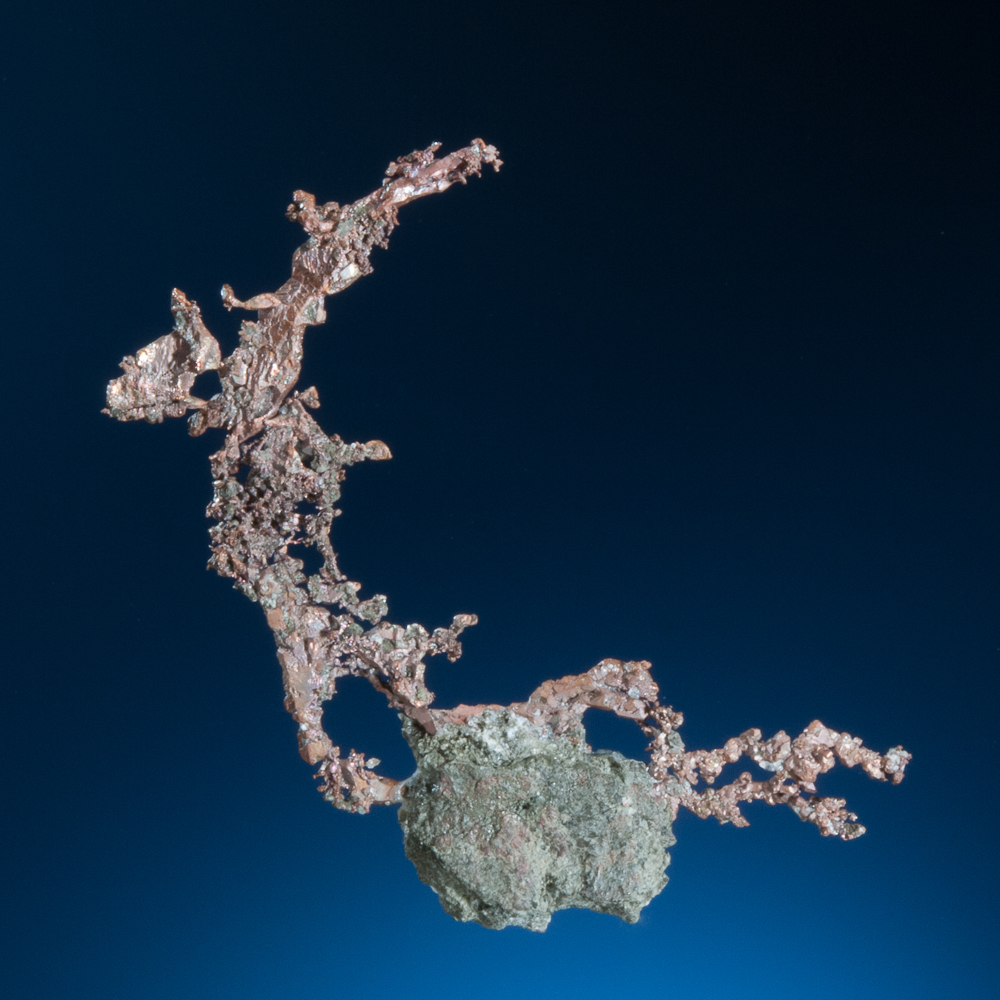

In recent years, Cap D’Or has perhaps best been known for the native copper specimens that have been collected from tight seams in one zone of basalt at the base of the cliffs. Some great crystallized copper specimens have been found.

As a locality note, there is more than one Cap D’Or copper occurrence, and the one that has produced many of the specimens (including the ones that follow) is on the shore near Bennet Brook and the historic workings of the Colonial Copper Mine. As a result, most labels use Bennet Brook or “Colonial Copper Mine” to identify that it is from these seams, where the mine workings are.

Copper, Bennet Brook, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – 8.3 cm

Copper, Bennet Brook, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – 8.3 cm

The fact that a number of these have been on the market might suggest two thoughts: (1) that they are easy to obtain, or (2) that they will become plentiful. I can personally confirm that the first thought is categorically false (!) and the second one is unlikely to become true. At present, a zone of exposed and fractured material yielding excellent copper specimens has been removed, and although copper can still be found, most of the remaining exposed rock is tight bedrock, with few signs of continuing copper at this time. (Hopefully the ocean will help a bit over time, but this is back from the usual reach of the waves, and even the metal detector isn’t encouraging, for now.)

In any event, I thought you might like me to illustrate my rejection of the “easy to obtain” idea. The copper occurs in narrow seams of celadonite cutting through the basalt. The basalt is solid stuff – when you are wailing away on it, it’s not something weathered or loose on the surface. You’ve hit solid Canada – hard rock. Meanwhile the copper is delicate, thin, and as if it is filigree. The copper is still very attached to Canada. A challenge, particularly if your goal is to remove the copper with a little bit of nice matrix!

To immerse yourself in the full Canadian-weather Cap D’Or experience in the next couple of photos, add a chilly wind, and note that the water in these photos is due to a cold November rain. (Yes, feel free to cue the Guns N’ Roses if you like, but there was no holding of candles.)

This photo shows nice crystallized copper, edge-on, in solid rock.

Copper in situ at Cap D’Or

Eventually, after a major effort, Terry Collett successfully extracted this section of copper, and here is a specimen:

Copper, Colonial Copper Mine, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – copper 4.8 cm across

Copper, Colonial Copper Mine, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – copper 4.8 cm across

One can work around a group of copper crystals, chiselling the hard rock as I did with this one…

Copper (about 3 cm) still attached to Canada, at Cap D’Or

Copper (about 3 cm) still attached to Canada, at Cap D’Or

… but ultimately after about an hour of hard work, the crystal aggregate sadly popped off with no matrix, and it was not as interesting as it looked like it might have been. C’est la vie!

Some nice specimens collected in recent years:

Copper, Cap D’Or, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 9.1 cm

Copper, Cap D’Or, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 9.1 cm

Copper, Cap D’Or, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 7.2 cm

Copper, Cap D’Or, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 7.2 cm

Copper, Colonial Copper Mine, Cape\ D’Or, Nova Scotia – 7.3 cm

Copper, Colonial Copper Mine, Cape\ D’Or, Nova Scotia – 7.3 cm

Copper, Colonial Copper Mine, Cape D’Or, Nova Scotia

Field of view 3.5 cm

Cape D’Or is known for fine specimens of many minerals, including the zeolites and associated species. Finds of particular interest have included thomsonite and some super stilbite epimorphs after mesolite.

Thomsonite-Ca, Cap D’Or, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia – 6.9 cm

Stilbite epimorph after mesolite, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – 7.0 cm

Stilbite epimorph after mesolite, Cap D’Or, Nova Scotia – 7.0 cm

As winter settles in, we all hope that over the coming months with the freeze-thaw cycles and storms, the cliffs at Cap D’Or will drop more nice, big mineralized blocks full of amazing crystal pockets down onto the beach, just in time for the next collecting season. (Who dreams of “sugarplums” for Christmas? I mean really. There are so many better things to dream about. Mmmmm… pockets of gleaming crystals…)

The End of Collecting Season

In most parts of Canada, November heralds the end of collecting season. There’s no need to bother telling this to the hardest-of-hard-core Bay of Fundy collectors because they will sometimes be out year-round, with equipment to facilitate climbing on the ice and snow (!). However, for Canadian collectors with local mineral localities inland from the coasts, the ground freezes solid, localities fill with solid ice and are buried in snow… we know the signs of late fall mean that it’s time to allow Canadian winter to run its course again.

White pine with early-November blueberry bushes above the Bay of Fundy,

in Cumberland County, Nova Scotia

About the Mineral Specimens in this Post

Many of the mineral specimens in this post are, or have recently been, available for sale on this website. I do my best to source Bay of Fundy minerals regularly, and to ensure that there are excellent specimens available (click here for Bay of Fundy Specimens).

I should note that the specimens photographed in this post (and the ones on the website at the above link) were collected by several people, including those mentioned in the next section, over years of visits to Bay of Fundy localities. While it is certainly possible to personally collect a good specimen during a visit, most of the specimens that come to light are the result of regular year-round visits to the most productive localities by a number of hard-working Nova Scotia mineral collectors. As with all mineral collecting, sometimes these visits produce fine specimens.

Thanks!

Just a quick note to express my thanks to some friends in the Nova Scotia mineral collecting community. To Terry Collett, with his encyclopedic Nova Scotia mineral knowledge and amazing memory – he may know almost every mineralized seam and outcrop along the Bay of Fundy. (It’s a bit scary.) An extraordinary field-collector and our generous friend in the field – thank you!

Terry Collett descending the ropes at Cape D’Or.

Terry Collett descending the ropes at Cape D’Or.

(Photographing wildlife – always challenging – is easier than catching Terry in a sharp still photo,

thanks to his enthusiasm and energetic speed when out field collecting.)

Thanks to Ronnie Van Dommelen for hosting us to learn from your amazing collection, and for making so much superb Nova Scotia mineral information available to all of us on your definitive Nova Scotia mineralogy website (please see References below). Thanks to another well-known superb field collector, Doug Wilson, for great time at Wasson’s Bluff (Doug and Jackie run the Amethyst Boutique in Parrsboro) and of course for all of your hospitality.

Thanks to Dino Nardini (who runs Nova Scotia Agate) for hosting our collection visit.

And thank you very much to Rod and Helen Tyson (Tyson’s Fine Minerals, in Parrsboro) for your warm hospitality.

As always, thanks to Dave Joyce, for all that goes into our adventures. (For the contributed photos too!)

Links

Part 2: Mineral Collecting on the Islands, Bay of Fundy (click here)

Mineral Specimens from Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy currently available for sale (click here)

IMPORTANT NOTE:

Please Use Caution!

There are serious accidents every year along the Bay of Fundy. Provincial emergency rescue teams are required to respond to evacuate hikers and others, and unfortunately these stories do not always have happy endings. People have lost their lives here. It may look gentle and mild in some of the photographs here (taken on the calmest of days), but absolutely don’t underestimate it – please be careful if you ever visit.

Any arrangements in this area must be made with careful consideration of the tide times and the weather conditions – mistakes in this regard can literally be fatal. Weather conditions on the Bay of Fundy can change incredibly rapidly. One must always have an eye on the time, the tide and the weather: always have a plan for managing a safe exit.

No visit to any Bay of Fundy locality should ever be made alone. Even some of the most careful, experienced Bay of Fundy mineral collectors have required the assistance of one or more additional persons to safely exit a Bay of Fundy mineral locality, either due to injuries or storms.

Many of the trails and access areas are steep and dangerous. The beach cobbles and shore bedrock can be super-slippery, particularly when wet. As between the trails and the shorelines, I think we’ve all fallen somewhere at some point along the way on these excursions.

Use of many of the access trails should not be undertaken without an accompanying guide.

The rocks comprising the cliffs along the Bay of Fundy can be loose and very unstable – some of the rock units are particularly weak. Always wear a hard hat and do not climb the cliffs.

Most of the collecting localities along the Bay of Fundy are unsafe and are certainly not appropriate for children. Beach collecting in a few of the very easy-access beach areas on the Bay of Fundy, away from cliffs, may be fine for children of an appropriate age, provided that it is conducted with continuous adult supervision to ensure, among other things, careful observation of the tides and avoidance of the strong undercurrents that can occur all around the Bay of Fundy.

This post does not constitute advice or recommendation to travel to the localities mentioned, and any decision to do so is each person’s own risk and responsibility. Adherence to applicable law and respect of private property are fundamental, and each of us is individually responsible – for ourselves, families and friends, and to the mineral collecting community as a whole – to be compliant and respectful at all times. If you are crossing or conducting any activity on private property, appropriate permissions must be obtained.

References

If you would like to read more about Nova Scotia minerals or research Nova Scotia mineral localities (including beyond the Bay of Fundy), I highly recommend Ronnie Van Dommelen’s great website, The Mineralogy of Nova Scotia

For additional reading, see also Van Dommelen, R. and Collett, T., “An Introduction to Minerals in Nova Scotia and a Report on Recent Collecting” in Rocks and Minerals 81:1 (Jan/Feb 2006), pp. 54-61